This article was originally published in the Fall issue of Bostonia Magazine 1992 and is reproduced with their kind permission .

EXCELLENT TEACHERS

The 1992 Metcalf Cup and Prize for Excellence in Teaching, Boston University’s highest teaching honor, was awarded to Professor of English William Vance and Professor of Music Anthony di Bonaventura

Beethoven’s Legacy - by Natalie Jacobson McCracken

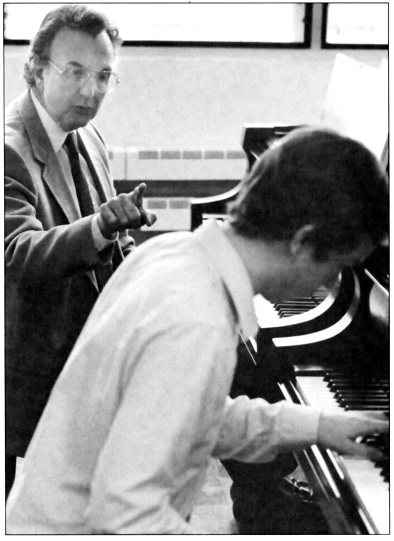

They sit at side-by-side grand pianos, the younger man playing Ravel’s intricate Miroirs, the other, his eyes on the score before him, listening with an intensity that is much a presence in the studio as is the apparently flawless music. Tipped back, his own legs substituting for the two front legs of the chair, he responds almost imperceptibly to what he is hearing, his head and occasionally his fingers moving with the glorious sound. Otherwise, he is motionless until he moves forward to turn the page. At pauses, this concentration is as sustained as the pianist’s. Anthony di Bonaventura is giving a lesson.

The music ends. Claude Labelle, one of the two piano students in the elite Artists Diploma Program at the School for the Arts, turns to his teacher. “Very good, Claude,” Professor di Bonaventura says; “Very good; really, very, very good.” He begins his detailed commentary. “Here, take the pedal off before the second beat. It becomes too cloudy otherwise.” “A little too elegant.” “I wouldn’t arrive here with the same level you’ve been working with.” Some comments are compliments; some, suggestions; some, instructions. All are clear and cordial, one is tempted to say courtly. Sometimes the professor plays a few notes; sometimes the student plays, Professor di Bonaventura singing along, “da da dadadada.” “Very effective, very good now,” he says and moves on. His praise, his corrections, and Mr. Labelle’s responses are brief. Shared goals, deep mutual respect and eloquent music make anything more superfluous.

Anthony di Bonaventura had long rejected teaching more than a few private students as detrimental to his well-established concert career when, in 1972, he was offered a position at SFA because John Silber was beginning his presidency of Boston University by recruiting the best faculty. “Having witnessed firsthand the deplorable level of teaching in some of the so-called first-rate music schools and their ill-prepared graduates who would go on to perpetuate their inadequacies, I decided then and there that Boston University, with such enlightened leadership, could be a leader,” Professor di Bonaventura wrote recently. “My own sense of mission was crystallized.”

He was inspired by his own great teacher, Madame Isabelle Vengerova, for whom he had auditioned when he was “a pretty cocky sixteen.” That confidence was well founded: he had given his first professional concert at four, won a scholarship to the Music School Settlement in New York at six, and soloed with the New York Philharmonic at thirteen. “I knew somehow I wanted, I needed to study with Madame Vengerova,” he says. “Being cocky, I wasn’t surprised when she said in a thick Russian accent [which he reproduces], ‘I will take you as my student.’ She also said, almost in passing, ‘But then you must play my way.’ I thought, ‘Fine.’”

He quickly discovered that meant unlearning all he had learned. She forbad his playing music. For a year, he was allowed only exercises; then, “in my more advanced stage,” scales. “I nearly went batty. I had given up what I had, but I hadn’t arrived anywhere. I was in limbo.”

One memory from the second year is particularly vivid. He had practiced a C minor scales three hours a day, every day for a week. “I played it for her and waited. I was in such awe of her. I couldn’t even look at her. I stared down at the piano and waited. Finally she said [again in the Russian accent], ‘Terrible, terrible. You cannot play. You must be a shoemaker.’ I was in New York, and going home on the subway, I thought, ‘Then I must end it all, throw myself under the subway.’ Luckily, human nature takes over; it says, ‘Wait a minute, maybe you haven’t practiced enough.’”

He kept practicing. Clearly he was among the most select of her select students, seeing her weekly rather than studying with one of her assistants, as was customary. After the second year – “the most painful period of my life” – she began assigning him music. Then, “at the end of one lesson she said, ‘And what will you bring next week?’ I knew, Wow! I’d arrived: I was going to choose.

“It was five years from the beginning before I began to feel comfortable playing. If anyone had asked me when I was sixteen if I would wait five years, I would have said, ‘What for?’ I was already satisfied; I thought I just needed a little polish. At the end, if anyone had asked, I would have said, ‘What’s five years?’”

He continued studying with her as a student at the Curtis Institute. Having graduated from Curtis with highest honors, he launched a career which has taken him to twenty-seven countries and appearances with orchestras that include the New York Philharmonic, the Royal Philharmonic, the Philadelphia Orchestra, and the Vienna Symphony; on Lincoln Center’s Great Performers series; and at major music festivals in this country and abroad. Reviews of his concerts and recordings speak almost in passing of technical perfection (the Boston Globe once described exceptionally complex Liszt passages as flawlessly “tossed . . . with the playfulness of Chico Marx”), then turn to more sweeping superlatives: “a real genius” (Zurich), “profound musical knowledge (Rome), “a sense of re-recreation that only the highest art can achieve” (Australia).

Today his professional time is divided about evenly between performing and teaching: “I wouldn’t do one without the other,” he says. His SFA students are generally in graduate programs; in addition, he teaches privately and in the summer in Main, at the Colby College’s Piano Institute, which he founded and directs.

The first goal of his teaching remains “to propagate what Madame Vengerova taught.” His method is, however, generally less severe Although some private students choose to spend their first year or two playing only exercises and scales, with his SFA students, “I do not try to do radical alterations. That would be unfair; they were accepted at the University.”

Still, what he teaches is “about 99.9 percent new to them.” He talks about “the unity of the body” and encourages them to play “not just with fingers but with their whole body; that is astonishing to most.” And he teaches them to listen. “When they really begin to hear, they are almost invariably disappointed by concerts. They go to hear someone with an international reputation, and they come back and say, ‘He was just sitting up there playing!’ They’re shocked.” Playing is only a part of Professor di Bonaventura’s lesson; he also teaches students to understand the music and the creative intent of its composer. “That’s not something you can learn sitting in front of the piano. There’s so much literature – especially about the Romantics – by composers and by people who heard them play. Sometimes students complain; they want to be playing and instead they’re at the library.”

Perhaps most astonishing, “I say to student, ‘The most important thing to have as a musician is not talent; it’s intelligence. Train your intelligence; your intelligence will train everything else.’ At Curtis it was a standing joke, if you’re looking for Tony di Bonaventura, don’t look in the practice studios, look in the library. My fellow students were practicing seven, eight hours a day. I’d stop to listen occasionally on my way to the library; they were working without a clear direction.”

That direction requires more than practice. “I stress that a serious musician must be a complete person. I tell students to experience life – go to the library, museums, football games. I’m always advising them to take liberal arts courses; a great strength of SFA is that it’s within a university with the total spectrum of courses to choose from. A few of them do. Generally the best are interested in everything.”

Studying with Professor di Bonaventura can “turn you inward,” an experience his students sometimes compare to Zen meditation, and which he found painful as a teenager. “But at the end of those five years with Madame Vengerova, I felt like a new person. I’d been through that tunnel, and now I saw things I had never seen. And that was just the beginning; I continued to change.” Long after they graduate, students call to tell him about their ongoing evolution. “They say, ‘Last year I realized what you taught me. If only I could come back and study with you again.’ Some do.”

As performers and teachers, his students “become conduits” for the music they play and for the approach Professor di Bonaventura has taught them. “Madame Vengerova once mentioned to me that I was part of the direct teaching link from Beethoven; i.e., Beethoven to Czerny to Leschetitzky to Vengerova and now to me,” he writes. “…It is a wonderful thought that Beethoven’s legacy will live on in my students and their musical progeny down through the ages.”